“Real pansori performers practice so hard that they spit up blood,” my Korean teacher, who tended to be exceptionally interested and well versed in art and history, asserted in class one day in 2012.

Whether a statement of fact or just one of the many benign national myths that I have encountered escaping from the mouths of foreign-language instructors in various countries, it was certainly enough to get me interested in pansori. Ten points for my teacher.

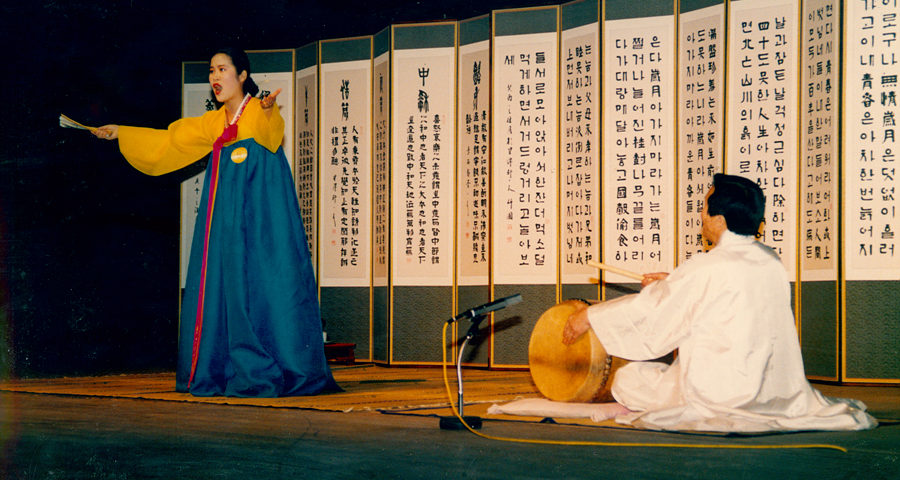

Pansori, a homegrown Korean musical style that literally means “sounds of the pan,” an open space used for community gatherings, consists of a (presumably very intense) main singer, called a guangdae (광대) or simply soriggun (소리꾼), usually a woman, who sing-chants a dramatic story, along with the accompaniment of a drummer, or gosu (고수). Her performance integrates narration (아니리/aniri), movement (발림/ballim), and, of course, extremely demanding singing over a wide vocal range (소리/sori). The art first began appearing within guilds of traveling performers during the Choseon period (1392-1897), but documentation of its origins and traditions was not consistent. As such, many of its productions, including seven of what are considered to be a canon of twelve performances, have been lost. [1]

The remaining five productions comprise a range of historical and fictional themes, from war and poverty to romance and talking rabbits. Spoiler alert. Chunhyangga (春香歌/춘향가) or “song of Chunhyang,” weaves social and political commentary into a story about a marriage to a local magistrate. [2] Jeokbeokga (赤壁歌/적벽가), or “song of the red cliff,” details the battle of the red cliff as immortalized in the Yuan/Ming Dynasty Chinese classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义/San Guo Yan Yi) or samgukji (三國志/삼국지) as it is known in Korea. [3] This is an enduring and culturally important legend also recently depicted in the 2009 Chinese blockbuster Red Cliff (赤壁/Chìbì). Simcheongga (沈淸歌/심청가), or “song of Simcheong,” is a tragic story about the familial love between an impoverished girl Simcheong and her blind father. [4] Heungboga (興甫歌/흥보가), or “Heungbo’s song,” is a series of tales about a common man and his many children, encompassing the very famous story of the kind-hearted but poor eponymous younger brother Heungbo and his greedy rich older brother Nolbu [5], whose impact on modern Korean culture can be seen in the many restaurants whose names ironically include his signifier (놀부). Finally, Sugungga (水宮歌/수궁가), or “song of the water palace,” is a satirical tale about a rabbit outsmarting a dragon king and his tortoise minister. [6]

Even if the stories behind pansori performances might be at once timeless and historically relevant, how can anyone sit and listen to one person alternately talking and singing for the three, five, even eight hours that one performance might take? one might wonder. They might then write off pansori as rigid, stuffy art for rigid, stuffy people with the time, patience, and refinement needed to sit in a dark theater listening for hours on end to abstruse configurations of words woven into tunes that are often not pleasant to the untrained ear, without even the benefit of elaborate scenery, costumes, pyrotechnics, and exciting orchestral music offered by European opera. Just a wailing woman in a white dress. And a guy beating on a drum. For half a workday.

But such a train of thought would belie the inappropriate assumption that older forms of performance art were always enjoyed in a way similar to that which they are today: In quiet, enclosed environments of minimal distraction, commanding the nearly complete focus of the audience. This, however, is not the case.

Just like the long, plodding, and highly stylized productions of Peking Opera (京剧/jingju) [7] and its cousins in China, Japanese traditional dances (日本舞踊/nihon buyu or にちぶ/nichibu) [3] and other stage performances in Japan, and myriad other forms of performance art that, at first glance, appear too inaccessible to stomach for five minutes, let alone five hours, pansori was originally enjoyed in settings in which it was perfectly acceptable for audience members to come and go at will and even talk and eat during performances. In fact, the “pan” in “pansori” derives from the fact that this art was first developed at local festivals on fairgrounds called noripan (노리판) where spectators freely moved from one attraction to another while enjoying the company and conversation of friends. Furthermore, performances are meant to be interactive, with audience members shouting out chuimsae (추임새), or words of encouragement like “jota (j좋다/good)!” and “eolshigu (얼씨구/hooray)!”, alongside the gosu (고수). [1]

So don’t be intimidated by the length of pansori performances, initial obscurity of their style, and, er, potential laryngeal ejaculations of blood from the performers. Do a search on YouTube, listen to a CD, or check out a live performance and take these musical dramatizations of our shared concerns as a human species as they were meant to be—-casually, with a sense of fun, and as a respite from the stress, grind, and ennui of daily life.

Non-Linked References

[7] Goldstein, J. (2003). From Teahouse to Playhouse: Theaters as Social Texts in Early-Twentieth-Century China. The Journal of Asian Studies 62(3): 753-779. [8] Klens-Bigman, D. (Spring 1999). Nihon Buyo Happyokai. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism:139-148.

This article was originally written for The Silk Road Project, now I Dig Culture, an international media channel that explores human cultural diversity and exchange.